Predicting the Fed’s actions for fun and profit

Every eight weeks, a room full of economists in Washington D.C. makes a decision that ripples through global markets, mortgage rates, and trading floors. The Federal Reserve's interest rate announcements move trillions in assets and can make or break investment strategies overnight. Yet despite this immense influence, predicting these decisions remains part art, part science, and if you believe the tie color theorists - part fashion analysis. While traditional models rely on inflation data and GDP figures, prediction markets have emerged where retail traders bet real money on Fed outcomes, and the wisdom of the crowds sometimes proves more effective. But if so, can we measure it? And how can we piece together a trading strategy to take advantage of it?

If you’re already familiar with the Fed and FOMC, feel free to skip ahead to the discussion on Polymarket.

What’s the federal funds rate

The Federal Reserve is the central bank of the United States. Among other things, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meets twice a quarter to revise the federal funds rate, the rate at which banks loan to each other. This rate has implications not only for the national economy but for the global one as well. It is the ‘base’ rate from which pretty much all other rates are derived from.

Since the federal funds rate is such an important interest rate, people pay a lot of attention to it. Much has been written about how to find the ‘right’ rate, and about how to anticipate or predict its level. Classical financial canon would point to the Taylor rule, an equation which combines inflation, GDP and target rates to arrive at a best estimate of what the Fed rate should be at any point in time. More modern approaches include using NLP techniques on the statements made by the FOMC to gauge their intent. Finally, a third and perhaps most entertaining category of ‘models’ is one akin to reading tea leaves — I am referring here to the practice of attempting to match the colour of Fed chair Jerome Powell’s tie to various Fed actions: the theory goes that a purple tie indicates hawkishness, or raising rates and a blue one would signal dovishness, or a propensity to cut rates. In fact this practice goes back to the year 2000 when people tried to gauge the result of FOMC meetings based on the size of then Fed chair Alan Greenspan’s briefcase!

Onto more reliable approaches.

The Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) has developed a tool called FedWatch, which calculates the probabilities of the FOMC taking specific actions based on the prices of fed futures contracts. What are fed futures contracts? Derivative contracts whose payoff profile is determined by the fed funds rate at the time of their expiration. In a nutshell, they are priced at 100 less the fed funds rate, so if the rate is 5%, the price of the current month contract would be 95. In fact, this is how we can determine what amount of rate changes are “priced in” at a given moment. If the current rate is 4.5% for example (consistent with a futures contract price of 95.5), and the price of a contract in the second half of the year is 96, we can infer that the market is expecting 96 - 95.5 = 0.5 or 50 basis points of easing by the time of the futures contract expiration. Quotes for these contracts are available on the CME website and allow anyone to infer expectations about future rates.

The FedWatch model takes this idea a step further and combines the futures prices with a formula to derive probabilities of hikes, cuts and holds. Simplified, the formula looks something like this:

Where the is the effective fed funds rate, and we assume that the Fed cuts in 25 basis point increments. The probability of no hike would then of course be . The same logic would apply for a rate cut. Those interested can read more about the methodology here.

Overall, the model has a pretty good track record of predicting the right move. A recent paper has shown that the model correctly predicts the outcome of a FOMC meeting 88.4% of the time when considering its prediction 30 days from the meeting date. At 60 days before a meeting, the accuracy drops to 76.52% while at 90 days we’re looking at a 69.3% hit rate — still respectable by any means.

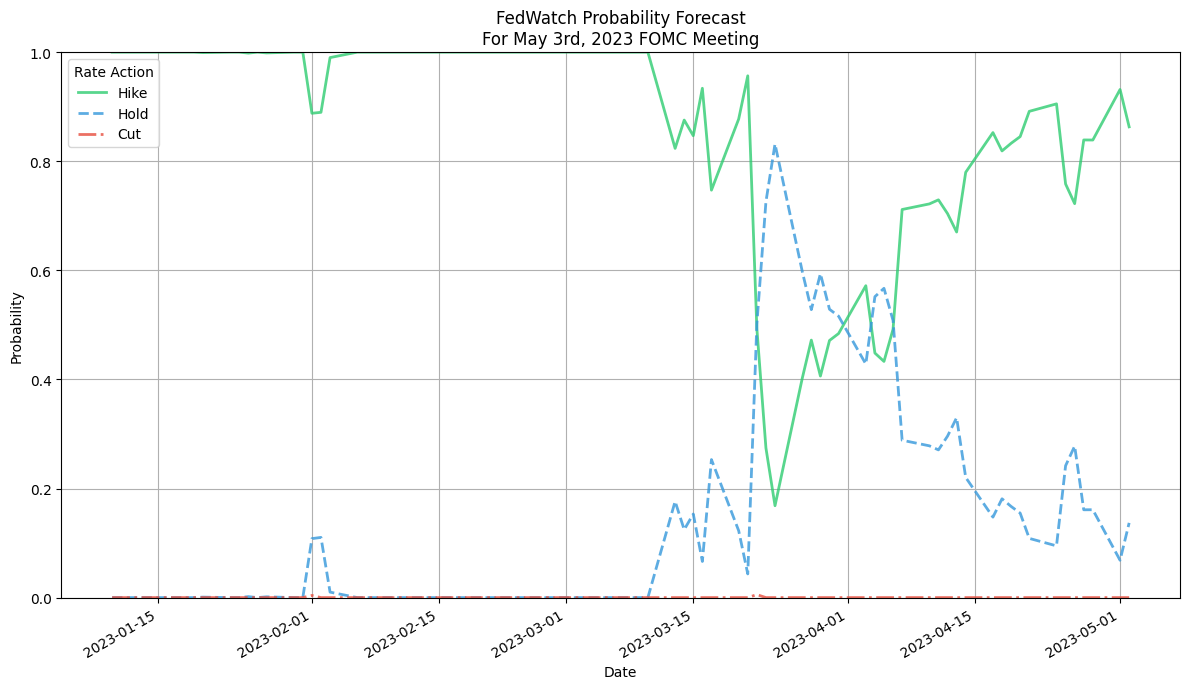

Let’s have a look at some example probabilities for a previous FOMC meeting:

The probabilities evolve over time and as the date of the meeting approaches, they also tend toward the correct action.

But this is not the only source. Indeed, the Atlanta branch of the Federal Reserve also publishes a model, dubbed the Market Probability Tracker, which uses SOFR option prices instead of relying solely on fed funds rates. Bloomberg users also have access to a World Interest Rate Probability (WIRP) function, which predicts rates based on fed funds futures - but requires access to a costly terminal.

Is this the best we can do

What about some alternative sources of information? Event contracts have been exploding in popularity recently, they are a straightforward type of derivative which allows people to bet on whether something will happen in the future. The payoff is decided by the probability of the event happening at the time of purchase. For example, one could bet on the results of a presidential election, weather patterns or, of course, FOMC actions. Brushing aside the already flimsy distinction between trading and gambling, these contracts represent a new source of information that we can use to infer FOMC expectations.

The largest prediction market at the moment is Polymarket. On this platform, traders (read: gamblers) buy and sell shares which represent the probability of an event occurring. For example, if they have a hunch that the Fed will cut rates at their next meeting, they can purchase a “share” of that outcome for the going market price at the time, let’s say 30 cents. If they are right, the value of their shares will be 1$ at expiration, allowing them to reap a 70 cent profit from their punt for every share bought. Given the nature of these markets, a price of 30 cents for such a contract would imply a 30% chance of that outcome happening.

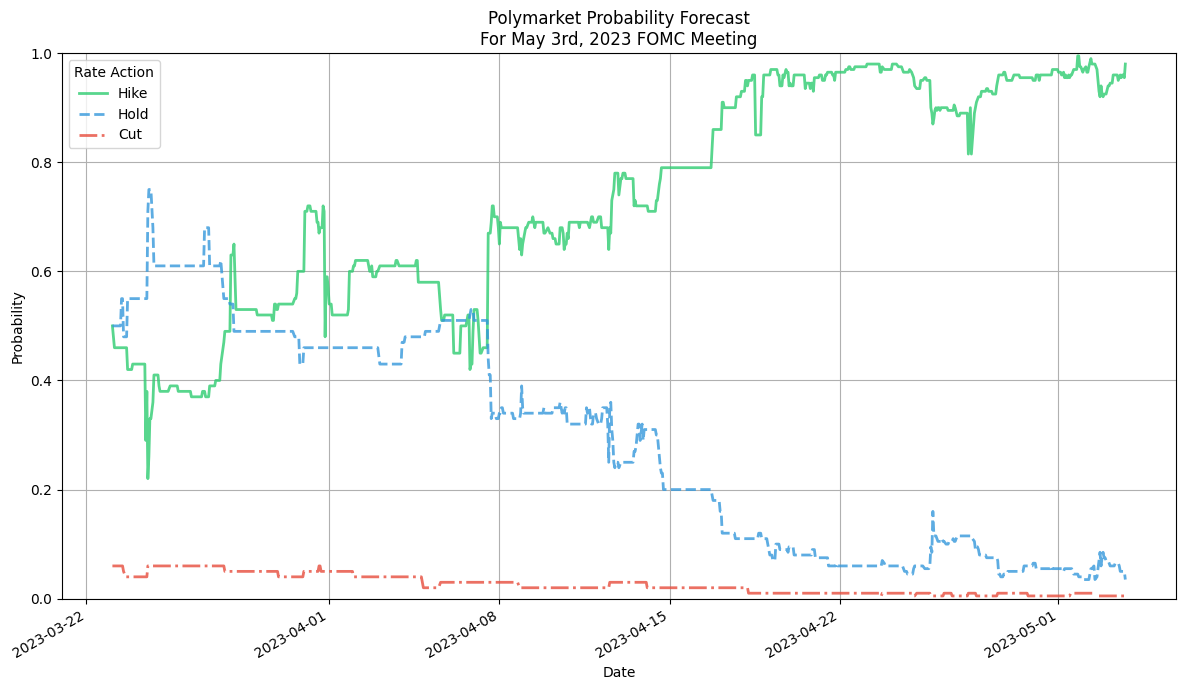

Let’s see the data for the same meeting that we looked at the FedWatch data for.

Now that’s a time series.

This leads us to the natural question - which market-implied probabilities are more accurate? The institutionally-driven FedWatch methodology (because fed funds futures are generally inaccessible to individual investors due to their large lot sizes and margin requirements) or the retail-driven event contract probabilities?

Because Polymarket is a relatively new platform, we only have the past few years of data on rate bets, so I’ll focus on the FOMC meetings from 2023 until today. While relatively short, this timeframe has seen a volatile macroeconomic environment, with high inflation lingering off the back half of 2022 as well as a rate hike, hold and cut cycle. This should make for fertile grounds for analysis.

Data digging

Getting access to Polymarket data was relatively straightforward, they expose most of their data through a series of freely queryable API endpoints. I’ll be focusing the analysis on the direction (rate hike or cut) of the FOMC decision, rather than the specific basis point increment that is being changed. This required a bit of data wrangling since the event markets are organized along two dimensions: by increment (25bps, 50bps) and by whether the event will happen (yes, no).

On the other hand, getting access to FedWatch data was not as simple. While the CME do advertise easy API access, the process actually involved creating an account with a business name, finding the API to add to my cart, creating an API ID to be able to access it, going back and forth with their customer support to get ID permissioned, changing my API ID to an OAuth ID before finally being able to hit their endpoint. Oh, and their API requires browser headers to be sent with every request (really).

Data in hand, let’s have a look at what it tells us, first for FedWatch:

| Days to meeting | No. meetings covered | Mean accuracy | Mean confidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 18 | 1.0 | 0.95 |

| 20 | 18 | 0.94 | 0.89 |

| 30 | 18 | 1.0 | 0.86 |

| 40 | 18 | 0.94 | 0.89 |

| 50 | 19 | 0.88 | 0.86 |

| 60 | 19 | 0.83 | 0.85 |

The further out from the meeting we are, the lower the prediction quality gets. The confidence metric decreases as well, but appears to stabilize towards the .85 level. Because the CME has a long data history, we can also see that the number of meetings covered for time checkpoint is relatively consistent - that is, they offer a sufficiently long data series for each meeting studied.

Turning now to Polymarket data:

| Days to meeting | No. meetings covered | Mean accuracy | Mean confidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 18 | 1.0 | 0.94 |

| 20 | 18 | 0.94 | 0.88 |

| 30 | 17 | 1.0 | 0.85 |

| 40 | 17 | 0.93 | 0.84 |

| 50 | 9 | 1.0 | 0.78 |

| 60 | 6 | 1.0 | 0.72 |

At first glance, the accuracy metric for Polymarket appears much better than FedWatch - however, this increased accuracy should be viewed together with the lower amount of meetings covered. That is, because the Polymarket dataset doesn’t stretch as far back in time, it would be wrong to take the accuracy metric at face value.

A simple accuracy comparison would lead us to a surprising conclusion. Both Polymarket probabilities as well as those implied by FedWatch have correctly predicted the directionality of FOMC actions 30 days out from the meeting itself. That is, if we calculate the probabilities of a hike, hold or a cut over time, and at the 30 day mark observe which of these is highest then both approaches perform equally well.

This initial comparison obscures a number of things however. The first is the “confidence” factor or how certain the predictions were at that point in time. In several cases the difference between one outcome or another was very small when it comes to the FedWatch model. An example would be in May of 2023 when the model was indicating a 57% chance of a hike versus a 43% chance of holding the rates steady — basically equating to a slightly weighted coin toss.

Indeed, by varying the prediction date up and down by 10 days for example, we lose the clean sheet and both models incorrectly predicted a hold in May 2023 when the Fed had actually hiked rates. For those who remember, this meeting was the first where Fed chair Jerome Powell signaled an end to the tightening cycle. As is known and often rediscovered in the world of finance, turning points are notoriously hard to predict.

Given the small sample size, the accuracy measurements also have wide confidence intervals. With 16 observations and assuming binomial distribution, a 100% accuracy rate has a 95% confidence interval of approximately [79%, 100%], meaning we cannot conclusively state that either method is systematically superior.

A strategy

Now that we have a handle on rates markets - what would the return of a strategy betting on these predictions look like? We’ll have to make some simplifying assumptions here, most importantly that the directional probabilities on Polymarket are the sums of the individual rate change probability markets. Concretely, we’ll treat the probabilities as follows:

This assumes independence between different increment sizes for the same direction, which may not perfectly reflect market dynamics but provides a reasonable approximation.

Our strategy will revolve around making bets on Polymarket based on the predictions of the FedWatch and the markets on the platform themselves.

Abstracting away the minimal transaction costs on the platform, as well as the slippage, we can define a demo strategy as giving a starting capital of $100. We take this capital and “full port” into the position that is indicated by the probabilities of Polymarket and the Fedwatch. An irresponsible approach for sure, but it will serve well to illustrate a point.

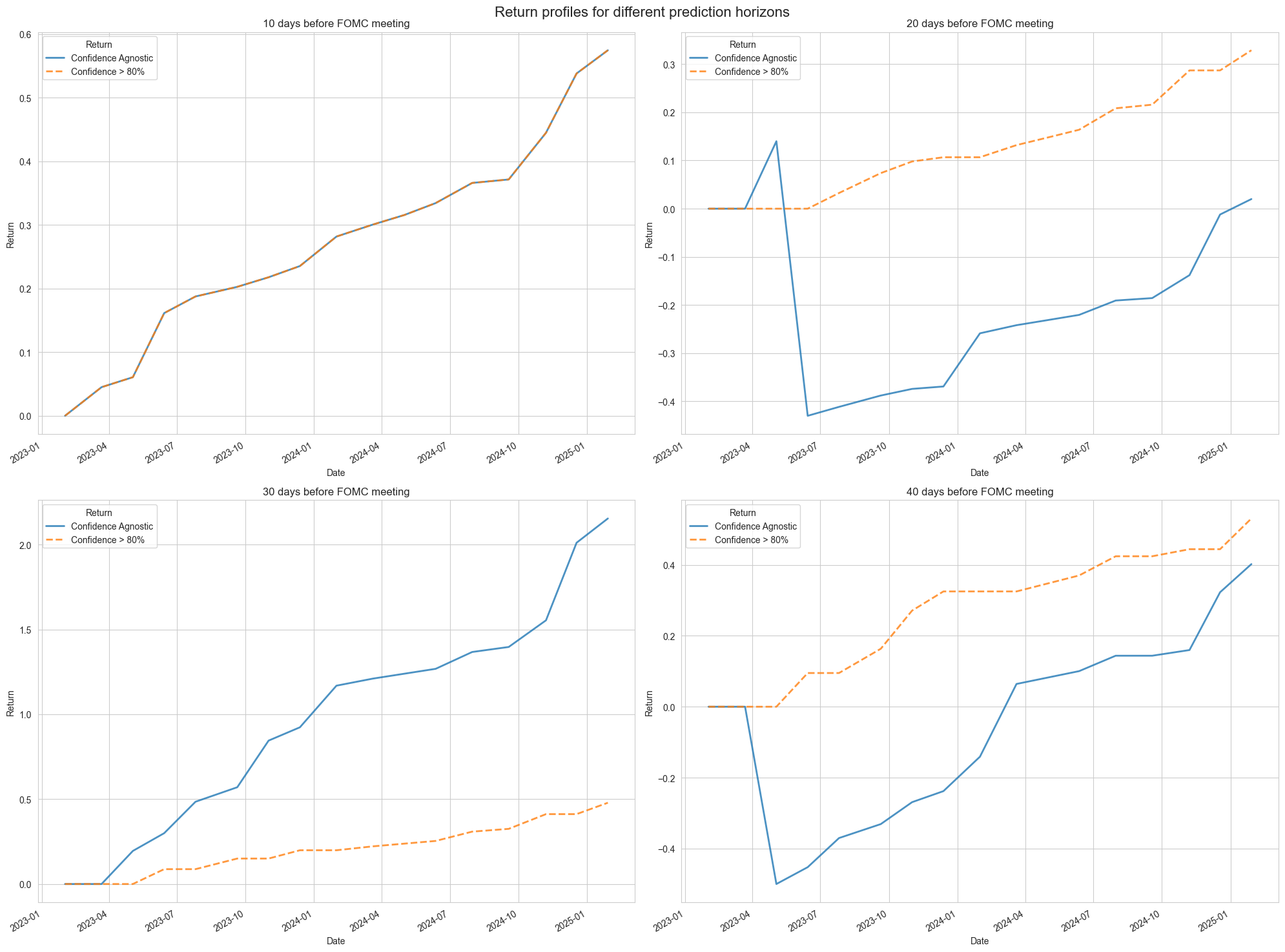

In the period from 2023-05-03 to 2025-01-29, following our strategy on Polymarket would have yielded a 781% (!!) return.

Of course, it would be hopelessly naive to believe that we would actually be able to return such figures. If our strategy would have been to bet on the most likely outcome 10 days out instead of 30, these returns would “cratered” down to 129% over the same period. And indeed if we would have chosen a 20 or 40-day timeframe instead, we would have lost the entirety of our principal capital due to one incorrect prediction. It is a common bias to assume the future will be like the past.

Let’s try refining our strategy a little bit. We have two directions at our disposal in which we can go. Firstly, we can see how the return profile is affected when we only allocate a subset (e.g., 50%) of our capital to each position. Secondly, we can lean into the confidence measure discussed previously and only decide to allocate when the markets indicate high confidence in a specific FOMC action. Let’s see what the returns would look like, depending on how many days before the meeting we decide to place our bets:

The returns paint an interesting picture. Off the bat, looking in the top left corner we can see that 10 days before the meeting the markets are relatively sure of their predictions, and we would get the same return regardless if we take into account the confidence level.

Where these two return profiles start diverging is where it gets interesting. On the right-hand side we can clearly see the perils of a wrong prediction. Of course, if the confidence level is lower, there is more to gain as well, but in our case it serves to barely eke out a net gain at the 20 day level. At the 40 day level we see an interesting performance with the confidence agnostic strategy almost catching up to the more cautious approach and yielding in the area of 40% returns over the time period. In both of these, the orange line exhibits a higher overall return and with less risk assumed, as we only bet on markets where the odds are relatively in our favor.

Finally, the 30 day plot in the lower left corner serves to bait us into thinking that is the best strategy. But the number of days chosen is more of an art than a science, and as we’ve explored with the rest of the plots, it can all come crashing down with one bad prediction.

Overall, adding the confidence filter serves to modulate the returns somewhat, while at the same time capping the strategy’s risk. Comparing the four, the 10-day approach looks the most interesting from a risk and return perspective. Assuming a risk-free rate of 4% (funny that we’re making assumptions about the very rate we’re trying to predict), we can calculate the Sharpe of this strategy to be around 2.1 - a very respectable profile and one that should warrant greater interest.

The long view

The beauty of these markets and strategies is that they are freely accessible to anyone with a few USDC in their wallet. A 60% return over a ~2 year period decomposes into a 26.5% annual return, which is pretty much identical to the annual return of the S&P 500 over the same time period. However it would be quite a stretch to assume this level of return can be maintained for a long amount of time in the future. Indeed, Polymarket has seen explosive user growth over this time period, which has served to close some of the opportunity gaps that previously existed in the Fed markets. While betting on rates is a riskier strategy that buying an index fund ETF, it offers an uncorrelated source of additional return which can be an interesting addition to a diversified portfolio.

This analysis does miss out on other factors which affect the Fed’s decision-making. Important economic data releases, government policy shifts and black swan events all play a role in shaping the central bank’s approach to setting interest rates. These should be at least acknowledged, if not outright modeled if one is to get a more comprehensive view on the rate-setting landscape. But that is research for another day.